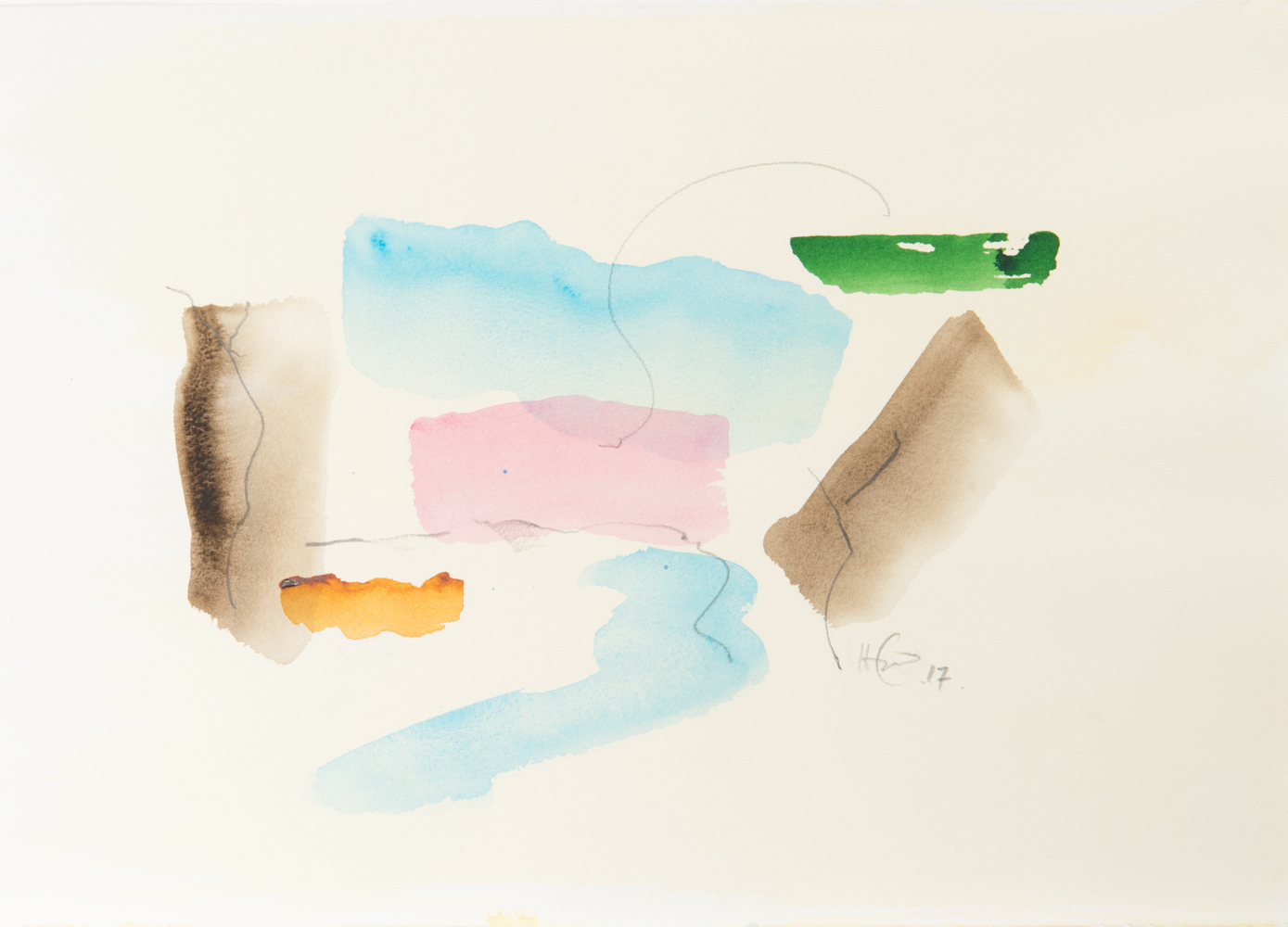

The Fairhurst Gallery presents Dual Jet Control an exhibition of drawings and paintings by renowned photographer Harry Cory Wright. The exhibition includes a selection of the artists lesser known works on paper which explore the North Norfolk salt marshes. Also on exhibition are Cory Wright’s new screen prints and one of his large-scale landscape photographs.

Cory Wright has been drawing with increasing intensity for the last 7 years. As a counter to the multiplicity afforded by the camera the artist is now looking to explore the landscape with the minimum of gesture; pen on paper and how the application of those gestures opens the door for coincidence and abstraction, aspects unavailable through his photographic process. It is this duality of intention and chance, control and abandon that offers new and fertile ground for Cory Wright with pen and paper.

‘Any landscape is a condition of the spirit.’ Henri Frédéric Amiel

A conversation between Harry Cory Wright and Nina Fowler, March 2018.

Photography

NF: You talk about the limitations of the camera despite its ability to document every minute detail. Your drawings are supremely simple yet they capture an essence of the landscape which your camera fails to do. How have your drawings informed your photographs?

HCW: I have always seen the big camera as being 100 percent literal… the closest thing to being there. There was no place for abstraction because it seemed to go against the acute recording ability of this highest end of analogue processes. Since the drawings however I have seen an opportunity to use the literal nature of the big camera and be looser with it, allow for some abstraction in the process but perhaps without completely shunning some of the inherent recording capabilities of the negative/film/print relationship. This rubbing together of two processes is appealing.

NF: Dual Jet Control – You have a physical hand in making your drawings and paintings which are not married to the printer on which your photos are created. Tell me about the difference in the control you have over your photographic images in comparison to the command of your drawings…

HCW: Well, you have spotted the conundrum that obsesses me at the moment… this desire to control the image in a highly design-orientated context, whilst being fascinated by the opportunities which a lack of control can offer. On the one hand the photographs are almost at the mercy of circumstance yet they convey, I hope, a sense of real order and harmony. The drawings on the other hand are best done with a sense of abandon; these are gestures made during a process of deep contemplation about a place.

This of course is the paradox that I hope is captured by the title of the show. The word jet is included as a reference to a recent obsession amongst a few of us on the coast of finding exquisite pieces of this gemstone in the landscape. Looking at its extraordinary polishable blackness is somehow very akin to the pleasure of a thin curved line of a creek in saltmarsh.

Landscape

NF: The works are produced in your houseboat upon leaving the landscape, where you will draw for up to 3 days having previously studied your compositions through the lens of a camera. Are these drawings something you need to almost ‘release’? Or are they more of a mediative, ‘zen-like’ process of considering something for a long time before executing them…

HCW: They are both. I find it hard to do the drawing ‘en plein air’ where the natural process for me is to take a photograph; to record. That process however, where I am trying to represent a line rather than specifically a place, does not suit the camera. A line, be it the curve of a shoreline, the bank of a creek whatever, can be so appealing and yet a photograph does not quite do it; the objective nature of the camera becomes restrictive. The drawings allow for an immersion based on experience and I am more interested by the distillation of experience over time, the amalgamation if you like. This suits me in a simple way but is also interesting to explore as it is the very opposite of what a camera is capable of with its 60th of a second.

Line

NF: You fashion your drawing tools – sharpening/flattening pieces of graphite in an

engineered approach to creating something which is quite the opposite. The result is a

complexity of line which can only be achieved with a highly practiced eye. Can you describe

the journey of your lines from conception to the mark made on the paper?

HCW: Oh boy, the preparation is endless… not in any disciplined way whatsoever. It’s just moving things around, sharpening things, laying stuff out, cutting paper, making tea, practicing lines. I have become very familiar with this process and now understand that there is a good relationship between this preparation and the simple and swift process of making the marks on the paper.

Edit

NF: Your photographic work involves much editing whereas your prolific drawing portfolio seems to have no boundaries when it comes to the edit. How do you modify your drawings?

HCW: As a photographer edit becomes second nature and I have no problem making things that are not right… that is part of the photographic process and one I like to apply to the drawings. In the days of 35mm film which had 36 exposures, the best frame would almost always be right at the beginning when the thought had just occurred, or somewhere in the middle when the working process built to a height only to be worn thin by the end. Making drawings with as few lines as possible is very much the same.

NF: I imagine working in the landscape to be a solitary practice. Working towards your exhibition and choosing which drawings to display, alongside producing your screen prints has very much been a ‘team’ project. Do you enjoy the break from autonomy which your drawings seem to allow?

HCW: Yes. Both the drawing and the photography are about being out there by yourself, then bringing back what you’ve seen to the gang. The second bit always benefits from involving other people… and of course it informs the first bit.

Paper

NF: Can you tell me about the paper stock you choose to work on. It creates an atmosphere within the landscapes of elegance and translucence. Does the paper decide/choose the landscape or vice versa?

HCW: For the most part I use an ivory Kozuke paper which is strong and fibrous but one side is quite smooth. I have tried many papers but this one seems to get just right the balance between absorbency whilst still allowing the pigments to hold themselves up on the surface of the paper. I find traditional watercolour paper much less immediate.

There is an extremely tactile quality to the Kozuke that feels good in the hand. The feel of the paper you are about to draw on as you place it on a surface dictates the landscape as much as anything… everything else.

Inspiration

NF: I am interested to know if you look to the work of other fine artists in developing your own practice or does the stimulation come completely from the landscape itself?

HCW: The representation of landscape through either photography or drawing is a language, one that evolves and grows all the time. It is crucial to stay up to speed with that language by learning from how other people use it. That is a beautifully unscientific process, thoroughly personal of course and without which you are probably just talking to yourself.

0 comments on “Dual Jet Control : Q & A with Harry Cory Wright”